Honor Culture

An Analysis Through History

If you would like to see the updated site with a navigation bar, click here!

During our talkback on Honor Culture, we listened to a podcast describing various situations that would come up in an honor culture. One instance involved a perceived challenge to the qualities of a teenage boy steering a motor vehicle, and responding by aggressively doubling down on the challenged behavior. The other, a much more public story about a french football star whom, on the final game of his career, got himself disqualified by attacking a member of the opposing team over an insult to his sister. As I listened further to the podcast, I became increasingly interested in the topic. Both because I recognised the similarities to experiences that I have had in my own life, and not leastways because I the foreign culture I choose to study (日本の文化) is sterotypically known for its cultural emphasis on honor. In this webpage, I'd like to take a look at the ways in which honor cultures permeate throughout American culture, in particular, the ways in which the ideals created by Honor Culture have shaped our country's political landscape, since its inception. I will be looking at three major events in American history, in which I believe honor cultures plunged us into conflict. Then, with a short program I will attempt to demonstrate how honor cultures continue to shape our understanding of American political life.

The Revolution

"Give me liberty, or give me death"

Many times have I made fun of the founding fathers' strong convictions about how the revolution was absolutely necessary. Compared to the rise of the fascist dictators in Europe during the 1930s and 40s (which will be discussed in part in the next section), it feels almost comical to start a war (mostly) over some taxes. Doubly so, when considering other parts of the world had it worse in terms of bad leaders in other parts of the world at the time. However funny these jokes are intended to be, they still fall victim to a rather presentistic view. After all, it assumes both knowledge of future events, and ready knowledge of events across the entire world.

But in an age where duels were commonplace ways of settling disputes between individuals (such as the one between Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr, an artist's rendition of which can be seen on the left), over personal disputes much smaller than how a government should be run, is this war really all that surprising? In the aforementioned podcast we listened to for class, they described those living in an honor culture as being utterly intolerant of anything perceived to be disrespect. As such, rather minor seeming disputes can become matters of life and death under the right circumstances. I would argue, that the circumstances preceding the revolution, were perceived as disrespect by the Patriots.

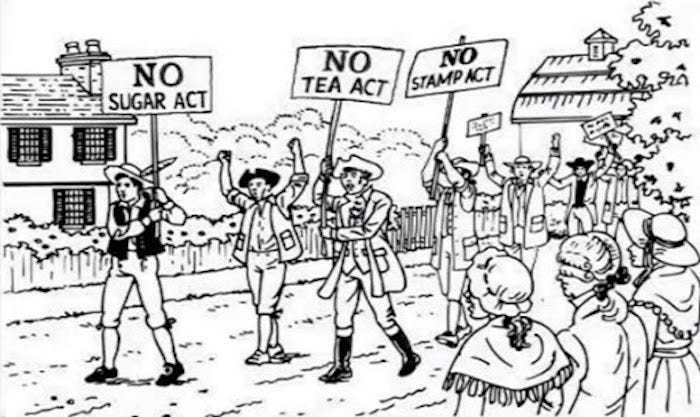

After all, the British were trying to make up for losses from a war the American colonists had no part in. Most of all, they were in no way impeding the war against the French, nor were they siding with them. As such, it seemed utterly disrespectful to ask them, the colonists, to fund the project. It should seem to those living in the American colonies, that the British were saying that they were less important than other colonies. After all, why shouldn't it be up to the citizens on the British island, the only ones with any kind of significant say in what wars were fought, that should have to pay for the war? This is what led to the protests (like the one pictured on the right), in which the Patriots would disparage the new stamp, tea, and sugar acts. Then, escalation. Rather than actually paying attention to the concerns of their citizens, the British took the protests as an insult, and began to try quelling these protests. This led to things like the Boston Massacre, soldier quartering in houses believed to hold meetings supporting the anti-british movements. As is typical of these kinds of escalations, this pushed both sides further into their loyalties. Honor Cultures pride themselves on the strength of an individual's displays of loyaly and bravery. This is how you get quotes like Patick Henry's famous "Give me liberty, or give me death." A display of principles loyal to the Patriots. While I agree with many of the principles that align with that of the Patriots, it is in no small way that I also see the point of Benjiman Franklin, who remained a loyalist until practically the very start of the revolution. Believing for a long time that, through determination, he could break through the pride of both the crown and the Crown and the Patriots to negotiate a compromise. Were more heads as cool as his, perhaps the war and death could have been avoided.

World War II

"A date which will live in infamy"

I shall try my best to make this section more brief, and I should like to preface this by saying that no part of this section is a defense of the empirial Japanese military. Rather, it is an exploration of the ways in which the United States utilized propaganda cause more people to enlist into being soldiers. It has long been propogated that the Japanese military commenced their attack on Pearl Harbor as a way of deterring the United States from entering the war in the Pacific. This is a somewhat disingenuous claim. Anyone with a rudimentary knowledge of American feeling towards the war at the time knows that most citizens were not interested in joining the war in either theater anyway. Instead viewing the conflicts as a problem for the people living in the area to solve. So, why then would the Japanese military decide to deploy any sort of deterrent upon a nation, that already had no plans to enter the conflict? The answer is simple: they wouldn't. The Japanese military at the time was running out of the raw materials to feed their war machine, and needed to find a source for more. Unfortunately for them, the best source of the materials needed, was required going through or into the at the time American territory of the Philippines. Seeing as invading such a territory would inevitably bring the U.S. into the war anyway, and the entire U.S. Pacific naval force was docked together in the same place, they decided to try and slow the response time of the Americans by bombing the fleet.

However, it is easy to see how this view of the attack does not easily transfer into war propoganda. Not quite like claiming they did it to try and break the spirit of the American people. Or as a statement that Americans are either incapable or unwilling to protect their homeland. In an honor culture, protecting what is yours is big. Showing weakness, that you can be pushed around is a death sentence. So it would make sense to design your propoganda around the idea that the Japanese meant this as an act of disrespect, as opposed to an act done in fear of your immediate military response.

The Red Scare

"Each carries in himself the germ of death for society"

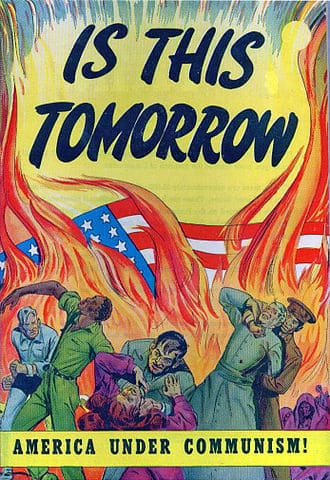

The Red Scare was not the first time in American history that those with a particular viewpoint would be viewed as dangerous and other. However it is, in my opinon, the attitude that has survived into our modern politics. As seen in propoganda on the left of this paragraph, Communism was seen as a herald of the end of the nation. As something that would inevitably lead to tyranny over the people of the United States and the destruction of all the values of the U.S. Instead of what it was: a different approach to economics. While I have always been rather unsure as to why the United States held their anti-communist viewpoint prior to the end of World War 2 (perhaps just more government involvment?), I feel like the difference in level of opposition before and after the war is clear. The friction that occured between Stalin and United States representatives during the war, was not going to be undone easily. Both sides felt slighted, and the people of the United States began to see not just Russia as the enemy, but Communists themselves.

Escalated by Soviet spies stealing information on new nuclear sciences, which led to the Soviets obtaining nuclear weapons earlier than anticipated, everyday citizens began to distrust each other's loyalty to their country. As president McCarthy came into power, all non-capitalists were now persona-non-grada. No longer were you just someone who felt a different economic approach might be better, your were now classified as "other." This led to people like J. Howard McGrath, the United States Attorney General, to make statements about Socialists/Communists such as, "...Each carries in himself the germ of death for society."

When I look at some of the more recent and extreme political stances we have looked at in class, and generally around today, quotes like McGrath's seem commonplace in today's political landscape. It is not uncommon to hear someone claim that someone's ideas are "unamerican" just because they align more closely with the right or the left. I would claim, that it is from the same "us and them" complex created by the red scare, that we see this today. I'd like you to take a moment to fill out the survey below, to collect data on this subject. (I feel obligated to mention, since this is on a real webserver, that nothing inputted will be saved.)